Note: The following is a rough and ready sort of mini-essay about theme parks and artificial environments. Specifically it is about the anxieties and fears of such worlds explored through science fiction. It is also looks at the spatial/architectural characteristics of such places.

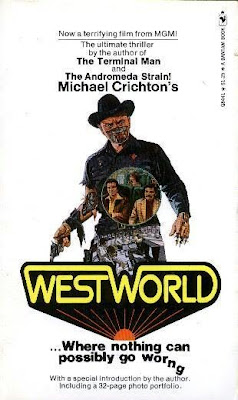

Westworld

The cult 1973 film Westworld, starring the fabulously strange Yul Brynner, is a classic piece of techno paranoia. The film depicts a futuristic world where intelligent machines develop a will of their own and turn on their human creators. But it is also about another kind of paranoia: the erosion of authentic experience through the creation of artificial or virtual worlds.

Westworld is set in a theme park called Delos which is divided into three historical zones: the Wild West, pre-Christian Rome and medieval Europe. Each zone is populated by robots who act as adversaries, sexual partners, drinking buddies or whatever else the human visitors require in order to have a good time. The guests - of whom there seem to be remarkably few - behave according to a crude, secondhand understanding of their chosen period, chasing after comely whenches in Medievalworld or starting bar-room brawls in Westworld. Behind the scenes an army of technicians programme, monitor and repair the robots.

The film makes heavy weather of the issue of authenticity from the off. A TV reporter appears in the opening scenes to tell us how real, genuine and historically convincing the zones are. Soothing female voices reiterate that visitors will be immersed fully in their historial epoch just as if they are really there. As well as a fear of losing control of technology, the film's underlying anxiety is the artificiality of the simulated experiences Delos offers.

The most obvious simulacra are the robots themselves which are physically indistinguishable from humans. This immediately implies a cruelty and amorality in the various ways that guests. abuse them. But the entire theme park is also a simulated, pre-programmed experience. implying a comparable abuse of nature*. The landscape of Westworld is the spatial equivalent of the robots: an image of nature overlaying a subterranean warren of blinking computer screens, cables, switches and technicians that maintain the illusion. In switching between the lab coated technicians and the theme park the film emphasises the prosthetic quality of this landscape.

Delos is presented as a completely immersive space with no sense of the exterior world. Guest arrive via plane where they are bathed in audio-visual simulations of the coming experience. Delos itself has no edge or obvious limits. The fact that it is actually located in the desert helps to blur this boundary when one of the guests escapes. This idea of an artificial environment that is hermetically sealed but whose limits cannot be gauged is a crucial aspect of all immersive worlds including the classic theme parks that Westworld satirises**.

Like the picturesque gardens of stately homes, theme parks are carefully composed to appear limitless. Boundaries with the outside world are dissolved through the artful placing of screens of trees, the arrangements of buildings and the use of ha-ha's.*** Arrival and departure is carefully regulated so that the park acts as an island, an environment that cannot be approached any other way than by the official route. In this way no sense of the outside world is allowed to impinge on the illusion.

A recurrent anxiety about theme parks is that this carefully controlled environment denies us the ability to act independently. To visit somewhere like Disneyworld is to take part in a minutely choreographed experience where little deviation is allowed from the script. This is most apparent in the rides themselves where the same experience is repeated for each guest exactly, ad infinitum, like a Fordist approach to having fun. But it also occurs in the landscape between the rides where boredom, lethargy or other forms of deviant behaviour is frowned upon. Cast members constantly coax visitors into immersing themselves more fully into the concept. These cast members, like the technicians in Westworld, have their own separate circulation system from the public, appearing fully dressed and smiling as if from nowhere.

Logan's Run

Logan's Run (1978) is set in a post-apocalyptic society. This society is - for reasons that become sinisterly apparent - entirely populated by attractive under 30 olds who live in an internal and artificial world. This world appears to its inhabitants to be limitless but is in fact contained within a series of vast interconnected domes, a kind of Buckminster Fuller dreamscape full of fabulous Brazilia style monuments connected by swooshing monorails.

The anti-hero Logan's understanding of the fundamental inhumanity of this society only occurs when he escapes its limits and realises that a world exists beyond it. This outside world contains only one inhabitant, an ancient old man somewhat bizarrely played by Peter Ustinov, who lives in the overgrown ruins of Washington DC.

The idea of a dystiopian world contained within a hermetically sealed dome parodies the utopian qualities the same structures assume within architectural discourse. Here the transparent, infinitely expandable dome stands for a kind of democratic, non-hierarchical space. It is an idea that runs through architecture from the early expressionists, through Buckminster Fuller to the '60's avant garde of Cedric Price and Archigram and on into '80's and '90's High Tech. The glass dome represents an anti-architectural fantasty of a physically dissolved building, reduced to providing (in Reyner Banham's words) a well-tempered environment.

Arguably, such spaces are derived from the Great Exhibition at Crystal Palace, another spectacular representation of the world within a single vaulted space. Exhibition spaces are not meant to have positive qualities in themselves. They are assumed to be both formally and literally transparent. And yet like the vitrine in contemporary art they are loaded with siginificance. Ironically the supposedly formless, transparent dome has become a symbol of immersive artificial worlds from Fuller's proposal for roofing over Manhattan to the Eden Centre. The glass dome is like a giant specimen jar. It is an object that contains species and objects we wish to study. The anxiety of science fiction like Logan's Run is that we have become the objects contained under the glass.

The Truman Show

Peter Weir's film The Truman Show is set in a fictional world created for a real time television show about its one genuine inhabitant, the eponymous Truman. As we discover at the end of the film, this world is contained within a vast domed environment. It is like an inverted panoptican, or a giant petri dish, with the whole world looking in. The film exploits a contemporary fear that all our lives are simulated, somehow no longer real but insperable from mediated experience. It also echoes Donna Haraway's arguement that we are all already cyborgs, prosthetically connected to the machines that we use.

One of the interesting things about the film is that this artificial experience is located not in a futuristic Blade Runner-esque environment - the familiar cinematic landscape of our fears - but in the genuine Floridian town of Seaside. This cheerful piece of New Urbanism - home to buildings by Leon Krier and Steven Holl amongst others - plays to architectural fears of artificiality and authenticity as well as a more popular suspicion that overtly cheerful and perfectly manicured places mask something sinister***.

When Truman discovers the truth of his artificial existence, he attempts to escape and comes up against the limits of this world in a scene of exquisite poignancy. Escaping by boat he drifts on and on under a perfect blue sky until he floats up to and then, gently, bumps into the edge of the dome that encloses the giant set. It is as unexpected to us watching it as it is to him. He slowly gropes his way around the edge until he realises that this is indeed the absolute limit of his world.

* The term nature is taken here at face value although it too is an artificial construction to some extent.

** Westworld was written and directed by Michael Crighton and is in some senses a forerunner to Jurassic Park, a film about another themed environment and another gross misuse of technology. Jurassic Park is the ultimate theme park, a genuine island of artificial species.

*** A ha-ha is a ditch which provides a physical barrier which doesn't disrupt the view.

**** If the film were made in the UK it would be set in Poundbury.

Final note: I would like at some point to extend this to look at game space and virtual worlds like Second Life.

1 comment:

I'm not sure which is creepier, the cinematic theme parks or the real thing.

Post a Comment