"I figured it out, that's all. Will you just listen?... Have you ever looked at something and it's crazy, and then you looked at it in another way and it's not crazy at all?... Don't be scared. Just don't be scared. I feel really good. Everything's gonna be all right. I haven't felt this good in years."

I watched Close Encounters of the Third Kind again the other day. It's a fabulous film in many ways, imbued with an almost lyrical technological optimism. Despite coming from a golden age of cinematic science-fiction, it's completely different in tone to anything else from the period. While Star Wars, for example, can be read as an allegory for the Cold War and America's struggle against another Evil Empire, Close Encounters is a plea for tolerance and understanding. Even the military appear relatively benign in it.

It can also be seen as having another, more unlikely, sub-text; one about issues of representation and communication. The film's central character is Roy Neary (played by Richard Dreyfus). Following a close encounter with an alien spaceship Roy becomes obsessed with visions of a strange, mountainous formation. He notices this shape everywhere: in the folds of his pillows, in the blob of aftershave in his hand and in a mound of mashed potatoes on his plate.

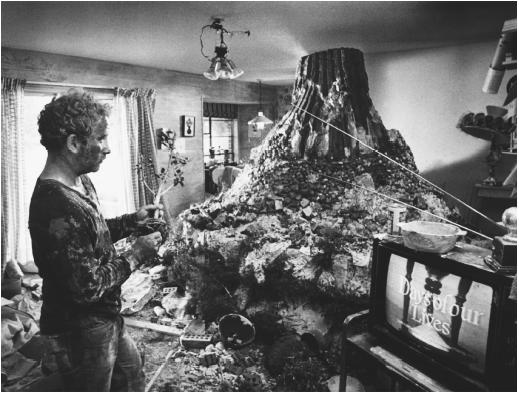

He starts to create maquettes of it in clay which become ever larger and more elaborate. Eventually, having alienated his entire family to the point where they move out, he creates an enormous model that fills his entire house. To make this model he ransacks the garden for materials, chucking them through a broken window into the living room to the horrified bemusement of his neighbours.

The resulting model is an utterly fabulous object, a grotesque assemblage of mud, vegetation, rubble, furniture and bits of string. It is both mimetically accurate (as we and Roy will later find out) and highly expressionistic, as if created by a bizarre hybrid of Robert Smithson, Jessica Stockholder and an acid-crazed model railway enthusiast.

Just as Roy is nearing the completion of this extraordinary object he realises what it means. The TV that he has blaring in the corner of the otherwise devastated living room has a news report about a bizarre shaped rocky outcrop in Wyoming. Roy looks at the footage of Devil's Tower and then back at his creation. He sits down in shock.

In some senses Roy is like a typically Hollywood-ian depiction of the artist: a half-crazed, anti-social lunatic in search of some intangible truth. Except he isn't an artist. Nor is he mad, just a little intense. And the film also wants us to take him seriously. His sculpture, as he repeatedly explains whist making it, really does mean something.

The film is obsessed with issues of representation and non-verbal communication. The famous five-note score that the scientists use to communicate with the aliens, for example, effectively replaces speech. The chief scientist is a Frenchman (played by film director François Truffaut) who makes no more than one or two gnomic utterances and is accompanied throughout the film by an ineffectual translator. The fact that none of the Americans can understand him seems to imbue him with some special understanding of what is going on.

Roy can't communicate his obsession through conventional language and is forced into non-verbal communication. He has to make what he is thinking in order to express it. And he's not alone in his obsession. Another character - Gillian Guiler - is also obsessed with Devil's Tower. She draws it over and over again. In a brilliant scene the two of them converge on Devil's Tower aware that it's the location for the alien spaceship's landing. Trying to work out how to scale the mountain Roy reveals that his knowledge of its topography is vastly superior to Gillian's. "You should try sculpture next time", he deadpans.

In making a plea for tolerance the film also seems to implicitly reject language, as if our primary means of communication were somehow ultimately a handicap to understanding. Language seems to dissolve during the film, becoming ever more useless until it dissipates into the abstract lights and sounds used by the scientists to communicate to the aliens. It is, in many ways, an anti-logocentric film, a celebration of the non-verbal and the techno-haptic.

2 comments:

When I saw it as a kid, I always found it kinda boring (until the end of course), but as the years have gone by I'm liking it more and more. It does have to be one of the strangest, most abstract 'blockbusters' ever made - with a strange sense of eroticism to the 'encounters' (a man loses his job and family in order to have a deep, mysterious 'affair' with the extraterrestrial). I think you hit the nail on the head on its theme of non-verbal communication.

There's also Spielberg's somewhat creepy motif of child abduction/abandonment (creepy in that these abductions are often depicted as 'benign' and liberating), which he's managed to insert into almost all his films since the 70s.

yes, and the non-verbal aspect can be seen as a typically Spielbergian veneration of childhood and "innocence".

Post a Comment