The concept of the zeitgeist is central to the rhetoric of modern architecture. The belief that buildings should embody the 'spirit of the age' assumes that they can be the logical outcome of the contemporary forces that bring them into being. Such a belief in modernity and in the duty of art and architecture to express the unique conditions of its own period is clearly antithetical to reconstruction. To be authentically modern, one can't recreate the past.

There can't be a site that better represents the vicissitudes of the twentieth century than Christ the Saviour. It lies in the centre of Moscow, close to the Kremlin and on the banks of the Moskva river. The original cathedral was constructed on this site in the mid-19th century. It was demolished in 1931 in order to make way for the enormous Palace of the Soviets. Only the foundations for this building were completed though and, after lying dormant for years, the site was turned into an open-air swimming pool. Then, in the last decade of the 20th century the cathedral was re-built, an immaculate copy of the original that was consecrated in August, 2000. To complete the return to a pre-revolutionary condition, the cathedral was the venue for the glorification of the last Russian Tsar as a saint.

In a sense, this story is almost too perfect an encapsulation of the retrogressive nature of reconstruction, far too neat a fable. The cathedral hasn't been rebuilt for any architectural qualities it might have had, although, like all cathedrals, it is impressive and awe inspiring when inside. It's reconstruction is a matter of attempting to erase the political events of the 20th century from the site, which from an architectural point of view seems a massive shame. The vast, circular Moksva swimming pool looked like a fabulous constructivist object, a gigantic circle from a Malevich painting spinning through the thixotropic space of the city.

Unlike books, or films, or paintings, a new building usually means the destruction of a previous one. Buildings replace each other, sometimes wrongly, and their conservation is a highly problematic issue because they always mean something to someone. In a sense, reconstructions compound the insult by demolishing the buildings that result from previous demolition. They attempt to rectify the violent erasure of the distant past by erasing the recent past.

The reconstruction of Christ the Saviour is an attempt to erase the crimes of Stalin, quite specifically as it was he who ordered the cathedrals destruction. Yet, re-writing history is a cliche of Stalinism. The re-built cathedral assumes that nothing of worth existed on the site and that nothing was lost in its reconstruction. The missing swimming pool has become like the people removed from official photographs and history books.

All of which assumes that buildings only exist in their physical form, rather than as a memory, or a photograph or a story. The Barcelona Pavlion only existed as such fragments for many years. It's canonic status within architectural history rested on a handful of black and white pictures and a few drawings. Arguably it's importance was, at least in part, a result of its inaccessibility. Buildings are sometimes more powerful in their absence. Certainly, its easier for a clear narrative to be developed when there is nothing left to contradict it. The perfection of the Barcelona Pavilion was preserved because, for fifty years, it never grew old. It's reconstruction allowed Robin Evans and others to reassess its qualities and contradictions, sometimes radically so.

It's hard to make a case against reconstruction on the grounds of being true to the zeitgeist. Such a position assumes a reductive relationship between technology and form. What happens for instance if the spirit of the age is nostalgic, or inherently reactionary? Ultimately, the argument against reconstruction might be same one as for any building. What does it replace and is it worth it? The Barcelona Pavilion replaced nothing but itself. The site had remained empty and the rotting foundations found in the ground were that of the original. It's tempting to suggest that these should have been retained as a ruin, a genuine preservation of the original. But this is simply another kind of sentimentality, an aestheticisation of the past that merely speaks to a melancholic rather than optimistic frame of mind. It's not so much the ersatz, or inauthentic nature of reconstruction that is the problem, more the futility of the gesture.

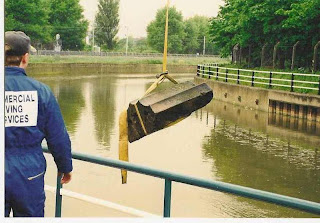

A restoration debate has been rumbling away in London these past few years. The Euston Arch was demolished in 1961 and, ever since, there has been a consistent campaign to have it rebuilt. Positions are polarised, and over rehearsed to the point of meaninglessness. But there's always been one detail I've found intriguing about the story which is that the stones from the original arch lie at the bottom of the River Lea. Parts of these remarkably well preserved columns and classical details have already been raised from the river. The proposal now is to literally rebuild using the salvaged material. No doubt if the plans go ahead the stones will be cleaned and repaired and the missing parts remade to complete the whole. As all reconstructions are representations of history though, maybe a more truthful picture would be to only use what can genuinely be reclaimed. The result, with its holes and gaps and stains might be a more compelling, and more genuine, record of the building's history.